Xeon 5500 (aka Nehalem) Marks the Death of Itanium (and More)

The last day of March 2009 Intel officially unveiled its brand new Nehalem core architecture under the Xeon 5500 product name umbrella. There is not much to say about it other than it's impressive from a performance perspective. Just to give you a sense of what we are talking about the new product - only available for 2-socket servers today and with up to 4 cores per socket - has published many benchmark numbers that are either on par or slightly better than 4-socket Intel based servers with up to as many as 24 cores. One might wonder why a successful (and clever) company like Intel is going to cannibalize their highly profitable multi-socket market with a lower profitable product such as the 5xxx Xeon series. And I think the answer to this question is in one of the slides they used to present Nehalem at the launch event:

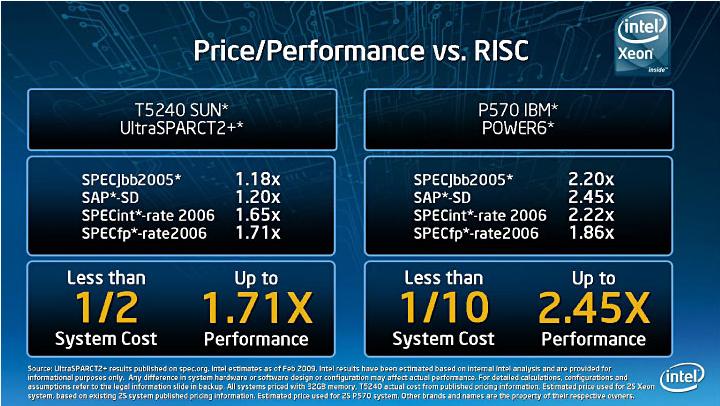

These numbers are impressive but I am pretty sure that if SUN and IBM marketing people would ever be able to read the small text at the bottom (which seems to be technically impossible) I am pretty sure they would come up with something to counter those numbers as they are obviously presented in a way that favors Intel; however I am not sure about this as I can't read the text myself so I don't know the assumptions behind those numbers. What it is important in this chart however is not the numbers (we know Nehalem has impressive performance per core) but it's the fact that Intel is now using Xeon to go after a 20+ Billion $ UNIX market. Up until now - and in the last 10 years - they would have been using Itanic (ehm... I mean Itanium... sorry for the typo) to go after the IBM Power or the SUN Sparc processors to get a slice of the Unix pie. This doesn't seem to be the case any longer. One might wonder where Itanium falls into all this: good question.

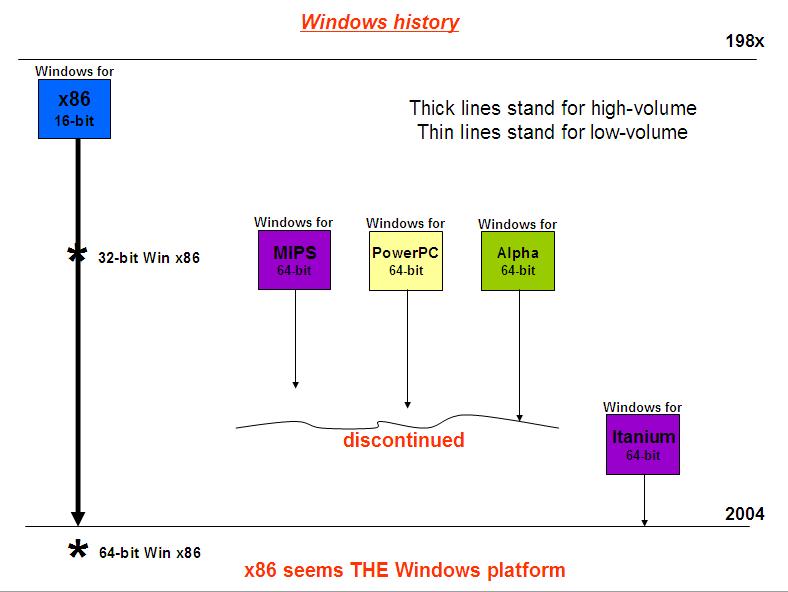

A bit of history on Itanium might help. Originally the Intel vision for the 64-bit Itanium was that it should have been the x86 32-bit follow-on product: the replacement for the Xeon brand basically. And they might have had a chance to succeed if AMD didn't come out with a much smarter evolution for x86 32-bit processors: in case you are wondering that would be an x86 64-bit architecture (namely AMD Opteron). When Intel understood they couldn't fight the Opteron with Itanium - since Opteron was 100% backward compatible with the Xeon software available whereas Itanium was basically not and would have required massive and painful applications porting - they decided to introduce the same "enhancements" to their Xeon processors. This was initially referred by Intel to as x86-32e: obviously they couldn't say Xeon was 64-bit as it would have overlapped too much with Itanium so they preferred to stay with the ridiculous definition of "32-bit Extended". This was the time where they tried to pitch Itanium as the only "native" 64-bit processor whereas the Xeon (as well as the Opteron obviously) were "just extensions to current 32-bit architectures". And this is when they shot themselves in the feet since they tried to play with the words (i.e. native sounds better than extended) but the only problem is that they forgot that, as far as IT is concerned, native means you have to port the application whereas extended means it's compatible. So, for most of the customers, eventually extended sounded much (much!) better than native. And this is when Itanium started to see its decline in perception. I did a presentation at an IBM System x Symposium in France back in 2004 where I have shared these thoughts. Interestingly enough at that time we had an Itanium based System x box in our portfolio - the x455 - and I basically implied that Itanium (hence the x455) was at a dead-end and a useless product given the historical context we were facing. This is for example a chart that I used in 2004 to predict Windows on Itanium had no real place and didn't make any sense at all; it took a while but I think now MS think along the same lines:

Funny enough there was an Intel representative in the room that apparently didn't like these messages and he decided to escalate and complain about my pitch to my line all the way to the General Manager of the IBM Systems and Technology Group (that reported directly to Lou Gerstner - CEO of IBM at that time). I was never been officially involved in this complaint but the fact is that, later in the year, we dropped the x455. I like to think I gave a hint to the product marketing team on what to do but more likely what I said in the session might have been a blessing from the field about what product management was going to do anyway (and for very good business reasons). For your information I have posted the entire Power Point deck in the Files session of my site if you want to have a look. You can download it here.

To make a long story short Intel had nothing left to do than re-position Itanium as a high-end RISC replacement with the help of HP that, confident in its value and roadmap, decided to completely drop their own RISC offering - the HP PA-RISC processor - and jump onto the Intel Itanium processor as a strategic replacement. Intel tried to position Itanium as an open platform mentioning they had dozens of OEMs offering servers based on that processors but usually they forget to mention that the vast majority of the sales numbers they were seeing were coming from HP which is the only tier 1 server vendor today offering such a processor (IBM and Dell used to but they withdrew it and SUN never even attempted to).

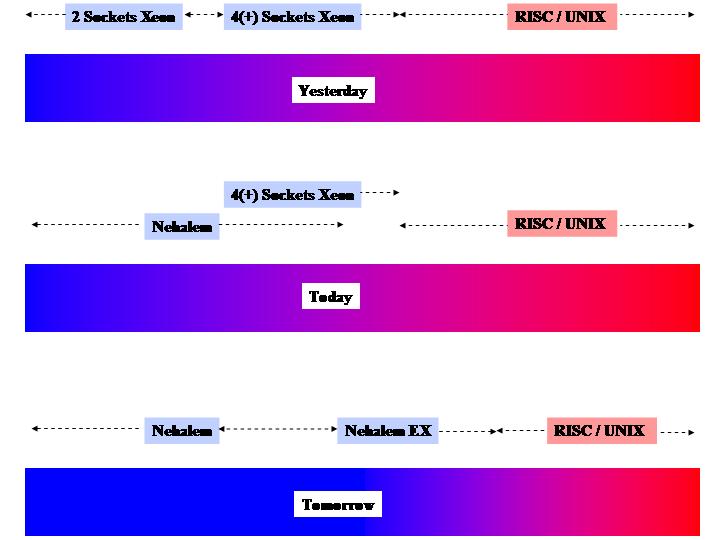

As Xeon (and the AMD Opteron) became more and more enterprise-ready, the Itanium potential started to shrink even further. Up until now when Nehalem seems to be the last nail on the Itanium coffin. Consider also that the first Nehalem incarnation is a CPU model for 2-socket servers (Xeon 5xxx). This might leave the impression that Itanium can address a much larger window as it shines on highly scalable boxes. The truth is that this is the first product iteration based on the Nehalem core. Later in the year Intel will announce a multi-socket Nehalem based CPU - aka Nehalem EX - capable of scaling up to 8 sockets (Xeon 7xxx series). This CPU will feature 8 cores and Hyper-Threading thus providing execution support for 128 simultaneous threads (8 sockets x 8 core x 2 threads) in a single system image. Last but not least this new CPU will also feature additional enterprise functionalities such as MCA (Machine Control Architecture) which was one of the few things Intel used to position Itanium as "more enterprise" than Xeon. On paper a system like this could address the need for 99.9% of the customers' requirements. This statement obviously refers to performance but we obviously all know that performance is just one aspect of platform selection. This will obviously cause some adjustments in the server market shares and this goes back to the fact that apparently Intel is cannibalizing their current high-end market. Most likely what they have in mind, instead, is that they want to push the bar further and enter even more aggressively into the UNIX market with a more appealing and serious offering (than Itanium) like Xeon. The idea is: I will cannibalize a high-end x86 profitable market today which is worth a few B$ with a lower-end and less profitable product, because I want to use its big brother (Nehalem EX) to go after a 20B$ UNIX market. Since a picture is worth 1000 words this is what I am trying to say:

Note that I am not implying this is what I think it will happen. As I said performance is just a metric in platform selection. I am only speculating on the view that Intel has going forward. I am not ruling out completely (either) that this view has a point given what's going on and if this happens this will not only impact Itanium in the RISC space but other UNIX platforms as well.

Back to the Itanium discussion, last but not least it's worth mentioning that there is going to be a convergence in the Itanium Tukwila time frame (unsurprisingly delayed again) where you can drop this new CPU into a Nehalem standard socket (see the Update below). Intel has always pictured this flexibility as a mean to lower Itanium development costs and make it more flexible/cheap for customers and OEMs to move from Xeon to Itanium. The reality is that at the end of the day you end up having a common system, with the same components, with the same CPU socket. At that point you'll have the choice of installing either a cheap, super fast Nehalem processor with an unmatched flexibility of OS flavours and ISV applications... or installing a more expensive, somewhat slow Itanium Tukwila processor with an embarrassing flexibility of choice of OSes and ISV applications (at least compared to the Xeon family). I am pretty sure there are some HP execs regretting the port of HP-UX onto Itanium rather than having ported it onto the x86 architecture - if they knew 10 years ago what the x86 architecture would have looked like 10 years later.

It's well known that not only Itanium didn't bring any profit but its development costs have been impressive and they never got on par with slow sales. In a word Intel has lost tons of money on Itanium. Having this said there are obviously a number of issues that prevent Intel from dropping immediately the dead processor: for example contracts that they have signed with "these dozens of OEMs" - and one in particular which I won't mention (again) - that dropped their in-house developed CPU architecture for jumping on Itanium. They cannot just say "hey we are dropping Itanium" and leave these vendors in the mud (especially one). So I guess it's fair to say that, officially, Itanium is alive and healthy, obviously you can imagine what the reality is.

Massimo.

Update (10th June 2009): while Tukwila and Nehalem EX will share the same QPI bus the sockets of the two processors will continue to remain incompatible for the moment.